Interview with Pianist Hélène Grimaud

by Peter Schlueer, Klassik Heute Magazine

Fulfillment of the Moment

At the age of fifteen she astonished the music world with readings of Rachmaninoff that set new standards. One wondered how the young girl from Southern France managed to storm through the rugged landscapes of the Etudes-Tableaux in such an evocative manner; from where she took the gloomy, opalescent power of suggestion and the wildly triumphing virtuosity for Rachmaninoff's colossal sonata op. 36 that she had learned within only three weeks. Shortly thereafter she turned her back on her teachers at the Conservatoire de Paris, gave her debuts at major festivals and surprised with colorful, impetuous interpretations of Chopin, Liszt and Schumann. An engagement with the Orchestre de Paris under Daniel Barenboim finally meant the breakthrough to a global career.

In her earnest search for substance and universality Hélène Grimaud found her way to a deep union with the music of Johannes Brahms. Her profound and thoughtful reading of the massive Second Piano Concerto with Vienna Philharmonic under Andris Nelsons, recorded in the acoustically superior Wiener Musikverein, is testament to her unique affinity with this composer. CDs of both Brahms piano concertos are available in new 2013 Deutsche Grammophon recordings.

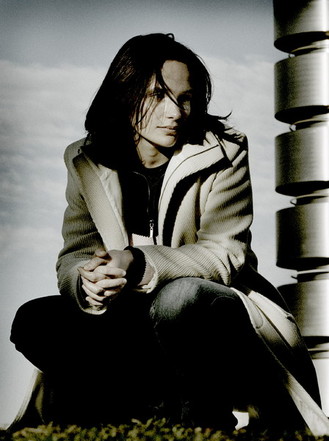

Today Hélène Grimaud lives in the United States where she keeps a pack of wolves in a big enclosure. She devotes as much time and energy to them as to the music. In her very personal relationship to the wolves she finds spiritual balance and collects new energy for her global concert tours. The wild animals form a deep source of inspiration for her art. In her secluded home north of New York she spoke with Peter Schlueer about how she became a pianist and about the mysterious connection of her musical philosophy with the originality of the wolves.

Peter Schlueer: You are the only musician in the Grimaud family. How come?

Hélène Grimaud: When I was a child my parents could sense that I was not really fulfilled, so they felt compelled to offer me a choice of activities. I was fine with school and liked

learning but I was troublesome about the process of learning and did it the way I liked to. I would always be finished first in class and then distract the others or bring up inappropriate subjects

that I was curious about. I was not interested in children of my age and hated the groups in which they gathered. They always needed a scapegoat which I found brutal and disgusting. In the breaks I

used to hide behind the refrigerator in the hall. I expressed my unfulfilledness and intensity in compulsive acts. I was obsessed with symmetry and sometimes would pull all my clothes out of the

closet to refold them using a ruler. It took me hours and hours and would drive my parents crazy. I did not find peace until this was completely in order. But what bothered them the most was that I

hurt myself deliberately: If something happened to me by accident, I had to have the same damage at the opposite side of my body as I could not stand to be off balance.

Peter Schlueer: What did your parents do?

Hélène Grimaud: They hoped that sports would help me. They tried to air my brain by offering me all kinds of activities but I was not really enthusiastic about anything. The last

thing that finally came to mind was music. And it stirred me up. So my father rented a small piano and organized a teacher. Music became my personal escape. It did not cure my problems but it helped

me to control them.

Peter Schlueer: What was intended to be a therapeutic aid unexpectedly revealed your greatest gift. You studied with Pierre Barbizet in Marseille and at the age of twelve entered the

Conservatoire in Paris to continue with Jacques Rouvier.

Hélène Grimaud: And at first everything went very well. But in my second year I started becoming rebellious. At the end of that year there was an exam in which you had to play

etudes. But I felt drawn to the big, musically demanding sonatas and concertos that were supposed to be played later. I wanted to put the cart before the horse! I was so bored by the F Major etude

from Op 10 by Chopin that I plain refused to play it. My teacher told me to either leave his class or play the etude. But that didn't impress me at all. I stayed away from the lessons and made my own

choice of repertoire by learning Chopin’s second concerto. Sometime later I performed it in public with members of the conservatory in Aix-en-Provence. Then I brought my teacher a recording of it

with the etude in question as an encore on it to prove to him that I had not been wasting my time. Some weeks later a producer from Denon came through Paris and wanted to do a record with me after

Jacques Rouvier had presented him that tape.

Peter Schlueer: A success achieved without any first prize at an international competition. Did you ever do one?

Hélène Grimaud: Yes, once. It turned out to be an important experience but it did not influence my career. At the Conservatoire it was expected to do competitions in the final phase

of studying. My teacher recommended that I take part in the Busoni Competition in Bolzano. But someday I found a booklet somewhere for the Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow and felt immediately drawn

to it. I absolutely had to go there since I had always been fascinated by Russian literature. I wanted to find out if the people there resembled the characters in the books of Dostoevsky and Tolstoy,

which I had read with great enthusiasm. My teacher Jacques Rouvier warned me it would be straight suicide for me to participate as I had no experience at all. On top of that he was supposed to be a

member of the jury and so would have to abstain from voting for me. Nevertheless I gathered my letters of recommendation and was admitted at the last moment. Although it was a bit hectic I managed to

prepare the imposed repertoire within the remaining time and was enthusiastic about the prospect of spending three weeks in Russia. I was so excited when I arrived in Moscow. I reached the

semifinals, learned a lot from listening to all the other participants, and made lots of contacts with people in the streets. Back in France, with some luck I was engaged for a recital at the music

festival of Aix- en-Provence. It was broadcasted on the radio and led to an engagement at the MIDEM in Cannes. Then Denon released my first CD with pieces of Rachmaninoff, and I met Daniel Barenboim

and played a concert with him and the Orchestre de Paris. He explained to me how dangerous it can be to waste too much time and energy on competitions and so this chapter had come to an end for me.

Sometime later I decided to quit my lessons and work on my own. I wanted to be independent and felt that I had by now received all the necessary tools from my teachers that I needed. Unfortunately

Jacques Rouvier felt personally offended by my decision. I am sorry for it because I owe him a lot.

Peter Schlueer: Did Jacques Rouvier teach you to practice slowly and without pedal like you do?

Hélène Grimaud: Yes. He wanted you to really listen to yourself, to develop the control of your ear, instead of just playing. It sounds self-evident, but it isn't. Most people don't listen to themselves at all. This practicing technique enables you to take in everything you need at once, and to process it better. It's so important to learn how to play legato or change tone colors without the pedal. Only once you can do that, you should put the pedal. And the more slowly you practice the more free you are when trying the original tempo. But sometimes I also work solely in my mind without the piano.

Peter Schlueer: How did you learn that?

Hélène Grimaud: Once I had to prepare a contemporary piece for an examination at the Conservatoire in Paris. I had no interest in it whatsoever and the day before the exam I did not even know the notes. After fruitlessly practicing on it for about three hours I decided to try something new. I turned off the lights, sat down on my bed and went through the beginning in my head. When I came to a blank I switched the lights on, carefully read the bars in question and played them a couple of times to learn the physical characteristics. Then I turned the lights off again, sat down on my bed and started anew. Five hours later I had better command over the piece than over any other of my program. It was a very important discovery that I continually developed further. Aside from the musical ideas that you can develop from mental work about phrasing or architecture you have to enhance the ability to physically produce the music by imagining the process of playing it in your mind. You hear the music in its greatest possible perfection and simultaneously your fingers as well as your whole body sense precisely how it would feel to ideally play it in that instant. It is a state of intense concentration in which you mentally project the act of playing into the future as an ideal scenario. On stage you can then follow this pattern as it is programmed in your mind.

Peter Schlueer: Does this detailed way of preparation also include your habit to arpeggiate chords in a subtle way and thus reveal their harmonic richness and colors which is one remarkable characteristic of your playing?

Hélène Grimaud: No, that happens more or less intuitively. When practicing I sometimes arpeggiate everything to hear the single voices. At times I fantasize about playing another instrument with only one line to focus on since the polyphony of the piano can be very frustrating. You never can do justice to all the details as too many things happen simultaneously. So you have to make a choice, which is always a compromise if you are aware of the variety of options.

Peter Schlueer: Do you have a preference in respect of playing solo or with orchestra?

Hélène Grimaud: To tell you the truth, recitals are much harder. They are more of an Odyssey, a journey of climbing the mountain on your own. A very stern and almost religious experience. I used to prefer concerts with orchestra because of the human element, because I felt stimulated by aiming for a musical goal together with others, being in the same boat. But being dependent on others also implies risks that can stand in the way of music, for example the level and the willingness of the orchestra and the conductor, or the very short time of rehearsing. This led me to enjoy the great and inspiring challenge of recitals more and more.

Peter Schlueer: You concentrate on a very demanding but limited repertoire. What is the philosophy behind that?

Hélène Grimaud: When I was young I took pleasure in the brilliance of the virtuoso literature. Today I feel far more drawn to the inexhaustibility of the great masterpieces. I'm not that much interested anymore in the dimension of the instrument itself. Today quality means more to me than quantity. If a work is substantial enough you can live with it forever. And even though it's not easy to constantly reconsider one's approach to a piece like Beethoven's sonata opus 110, this ultimately is the only sensible way of working for me. One always has to abstract from what has proven to be good in the previous concert. It's as if you consciously step back into a state of unconsciousness. It can be very dangerous to repeat something proven in an unreflected way. Each performance should be different from the previous one for a clearly defined reason. It was the violinist Gideon Kremer who taught me to constantly reflect on a piece and ask myself about the options of phrasing or coloring a musical detail. When we rehearsed together the first time he would uncompromisingly ask me about my musical choices in every single bar. It opened up a new world to me. It was the pivotal point that led me to approach a piece intellectually. At first I felt blocked by the variety of possibilities but then I learned to understand it as a complement of my intuition. The great masterpieces contain endless dimensions that let you grow while you work on them.

Peter Schlueer: Especially the great masterpieces of Brahms became a constant in your musical life. How did you find the key to this composer?

Hélène Grimaud: At first I had difficulties with his pianism, but from the start I felt a deep resonance. The Brahms piano concertos are amongst the finest works in the whole piano repertoire. The First Concerto is a rough diamond, a pure expression of the soul. I think of the first movement as a requiem, the second as a prayer, the third as a struggle which gradually gives way to acceptance of oneself and of the crises one has lived through, followed by the coda in which the soul can at last rejoice. The piece offers a very personal vision of the world. It has a quality of inwardness, of emotional tension, heartbreak. The music of Brahms struck some very personal cords inside of me. I identified him as the most direct successor of Bach and Beethoven. He is more classical, more contrapuntal, and more structured than any other romantic composer. And less narcissistic. I have the feeling that he directly led me to my current passion for Bach and Beethoven. It was an inevitable process: I began building bridges back to the origins of what had fascinated me in Brahms. There are two elements which I'm fascinated by in particular. Firstly his sense of rhythm. The rhythm pulsates like a constant heartbeat. The slow tempi never are really slow, just as the fast ones never are really fast. There is a dichotomy between concrete and abstract time, in which a great expressive complexity unfolds: A phenomenon that could be described by the contradictory idea of a 'timeless time'. The second element is this poignant quality of the emotional content, the way Brahms looks back into the past. There is nothing nostalgic about it. He seems to reflect on a moment when everything changed, and everything changed from the better to the worse. This gives such a tragic and poignant quality to his music and all of the sudden leads to something universal, to a constant of life that connects us all.

Peter Schlueer: Do the wolves also symbolize something universal for you?

Hélène Grimaud: Absolutely. Perhaps it is my desire for something more whole than the human species which connects my passion for music and wolves. We humans are everything but whole, our existence is limited by a countless number of compromises. Our senses are so stunted. Music or any artistic endeavor requires a great sharpness of the senses, of the original qualities of man. From this point of view music and wolves come very close. Many people do not seem to realize that. The deeper reality of what my two lives are is supplied by one source which is the aspect of originality and wholeness. The wolves taught me to understand the religion of the native Americans who see divine aspects in all of nature. Sometimes people ask me if I believe in god: I definitely believe in something that is beyond us, something we take part in. It is on stage that I feel the most religious, to whom or what I cannot say because I do not have an identity for what my religion would be. My best concerts I do not feel responsible for. I feel in a way that I have put myself in a position of being receptive and then something like a visit happens, which is quite a mystic feeling. In the case of Bach's music I think, god owes Bach a lot because without Bach's music many people would not know of god's existence. The music and the wolves complete each other. Together they make my life more whole. I regard it as a great privilege to be able to devote myself to both things.

Peter Schlueer: Would you say that you dedicate yourself rather to music and wolves than to other people?

Hélène Grimaud: My relation to other people oscillates between great interest in and sympathy for single individuals, faith in what they can accomplish, and total pessimism in regard of our species as a whole. As a species we are stupid and shortsighted. Most people do not look beyond their own little lives. When I get off stage sometimes I see that I have produced something on people, that people have gotten something from it. I used to not value that at all. I thought whatever an artist could give was not enough substantial to make an impact on anyone's life, unlike the work of a doctor or lawyer. Meanwhile I changed my mind a lot on that. At times there are fleeting moments in concerts when people can take off and all of a sudden find back to themselves or rediscover an immediacy that they had unlearned as civilized and controlled humans.

Peter Schlueer: Do you yourself experience this immediacy with the wolves?

Hélène Grimaud: Absolutely. The first time I experienced this was after I had moved to northern Florida. My new neighbors had warned me of a strange and dangerous man living at the edge of the woods: a Vietnam veteran keeping a wolf. One day we met by chance and had our first conversation. It turned out that he was a very fine guy, he loved classical music and had a big collection of records. During our chat the animal came to me although she normally would be petrified of strangers. The man told me about his fruitless attempts to socialize her and to establish a trustful relationship with her. When we met the third time the wolf would all of a sudden roll over for me and allow me to scratch her belly. She had never ever before behaved like this. The man explained to me that I had to understand this manifestation of affection as a great privilege. I spent more and more time at his place and looked after the wolf. One day she would signal her confidence in me by dropping a big chunk of ribs on my lap and go on crunching it there although wolves normally tend to be very protective of their food and aggressive when they eat. So I got really close to her and she did to me. I started to travel around and learn everything about wolves. I took seminars, ethology courses and made practical studies in zoos and wildlife preserves. After I had gathered enough knowledge and felt ready I applied for a license to keep wolves and the Vietnam veteran let me have the wolf as I had become the person that she trusted most. The first thing I did was to join another wolf with her.

Peter Schlueer: How many wolves have you got today?

Hélène Grimaud: Currently thirty. Meanwhile the enclosure has become an official preserve with the status of a non-profit organization which means that the project now can grow independently from me and my financial means. The purpose of it is research and public education. This means that biologists, ethologists and psychologists come here to do research work and that we offer introductions for private visitors. In the near future we will start a project with the Mexican wolf that is extinct from the wild. These wolves shall breed here and later be put out in the wild.

Peter Schlueer: What is the most essential thing that you learned from the wolves?

Hélène Grimaud: We civilized humans constantly ruminate on the past or dream ourselves into the future. That is why we are so dissatisfied with ourselves. Whereas the wolves live each moment to the fullest, like the eastern religions teach it. You can make a lot more out of life by doing that. We must realize that the only thing that we really have is the now, the fulfillment of the moment.

Peter Schlueer

LinkedIn